NSU students, professor part of research that could lead to cure for Huntington’s

While her friends are working typical summer jobs, Northern State University student Cindy Venegas is spending her summer conducting research for a project that could lead to a cure for Huntington’s disease.

“It’s very cool,” said Venegas, an Aberdeen native pursuing a bachelor’s degree in biology and an associate’s in biotechnology. “It’s amazing to be able to do research as a sophomore in college.”

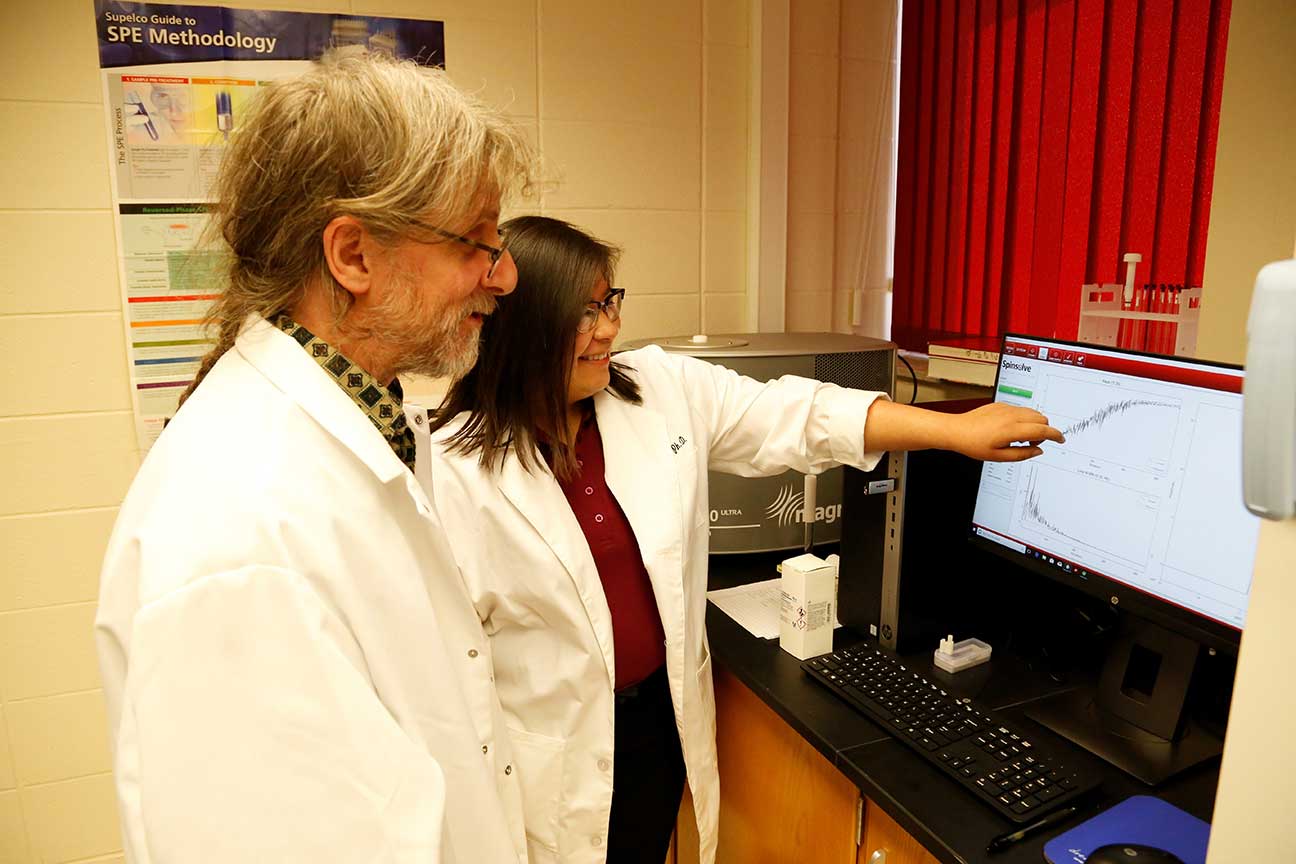

That’s an opportunity unique to NSU, said Dr. Jon Mitchell, who is working with Venegas.

“That’s the Northern advantage,” said Mitchell, associate professor of biology.

Mitchell and Venegas, along with NSU senior Zach Fleming, have been working for the past year to purify the sheep gangliocide GM1, which has been found to impact the effects of Huntington’s and potentially other neurodegenerative diseases.

It’s advanced research, Mitchell said, and it’s funded thanks to a South Dakota EPSCoR (Established Program to Stimulate Competitive Research) grant that pays for wages, equipment and materials.

“It doesn’t happen very often that students get the opportunity to get a little bit of a wage and do some hard science,” Mitchell said. “This is not easy stuff and no one’s doing it.”

Collaborative Effort

The work is a collaborative effort with Dr. Larry and Sue Holler of GlycoScience Research Inc. in Brookings. The couple own a flock of sheep, some of which carry a genetic trait (GM1) that may help people living with Huntington’s, Parkinson’s and Alzheimer’s diseases.

The GM1 gangliocide is critical for normal neuronal development, but in excess causes a genetic disease, Mitchell said. By the time the Hollers’ sheep turn five months old, they’re producing so much of this gangliocide that they cannot function, and they must be put down.

But for people with Huntington’s, research has found that injecting them with this GM1 gangliocide reverses the effects of the disease.

Working Toward a Cure

While this treatment is in very early stages, its impact is certain.

“It is a cure,” Venegas and Mitchell both said.

The Hollers are continuing their work toward getting GM1 approved by the Food and Drug Administration as a treatment. Mitchell and his students are doing their part by working on another component of the project: purifying the gangliocide to determine if the rest of the afflicted lamb is viable – namely, if the meat is safe to consume.

They’re using a couple of different monitoring approaches. In one, they use a fluorescent molecule that will bind to the GM1 to quantify the amount. The other method is standard biochemistry, Mitchell said, monitoring levels using NSU’s new nuclear magnetic resonance spectrometer. This piece of equipment was purchased thanks to a $52,991 Research and Development Innovation Grant from the South Dakota Board of Regents.

Future Possibilities

The GM1 project is ongoing, and they’re hoping EPSCoR funding will continue. They’re also hoping to gather data and eventually send Venegas to a nationwide meeting to present on the project.

Other future possibilities include actually making GM1. Only a sugar separates GM1 from other gangliocides, Venegas said, so if they can isolate the GM2 or GM3 gangliocides and move some of the sugars around, they might be able to make GM1.

Mitchell said their work has involved picking up blood samples from a sheep farmer in Forbes, N.D., and it’s great that the students are getting to see all aspects of research.

“You get to go out in the field, and you get to see it in the labs, and then you get to see the potential for helping folks,” he said. “You get to see the end product.”

Research Will Help with Career

Impacting people’s health is amazing, Venegas said, and is in the area of what she wants to do for a career. She hopes to attend the University of California, Berkeley, pursuing a master’s degree and Ph.D. in biological engineering, and possibly work in pharmaceuticals.

Her undergraduate research at Northern has given her a great start – and it’s an opportunity not found at all colleges.

“In bigger schools, you don’t really see that,” Venegas said, adding, “Actually doing hands-on stuff is pretty great.”